Jesse Tyson was a 30-year-old carpenter living in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, near what is now Fairmount Park. He joined the 88th Pennsylvania Infantry on August 29, 1861.

On the afternoon of September 16, 1862, the 88th Pennsylvania crossed Antietam Creek. The Union Army prepared for a fight but only skirmished until darkness fell. The 88th rested on their arms in a patch of woods just beyond the famous cornfield.

162 years ago today, the 88th Pennsylvania was ordered to fall in. When the sun first peeked above the horizon, the enemy’s cannon opened up.

From the regimental history of the 88th:

“Directly in front and to the right of the regiment was an immense cornfield occupied by the enemy, to whom the men sent their leaden compliments as fast as they could load and fire, the graybacks doing the same favor in return. A burning barn was fiercely blazing a little to the left, while to the right heavy lines of the enemy were in sight, apparently bearing heavily on the regiments farther to the right. The Confederates in the immediate front of the regiment were mostly concealed, and it was extremely difficult to get a fair shot at them, but their fire told very severely on the ranks of the command, the men dropping like autumn leaves in a storm.”

They pushed out of the woods and met with heavy resistance, eventually pushing them back.

At some point, Private Jesse Tyson joined more than 4,000 soldiers who lost their lives that day.

88th PA Private John Vautier wrote of Jesse in his diary:

"Visited the battleground again today. Saw the ground on which we fought. Saw the graves of our beloved and noble comrades who had sacrificed their lives…the ground is still red with their blood. I made a headboard for Jess Tyson’s grave, and wrote on it.

Jesse Tyson

Co. I 88th Regt. Penna. Vols.

Killed Sept. 17, 1862

A brave Soldier and Kind Comrade

Rest in Peace"

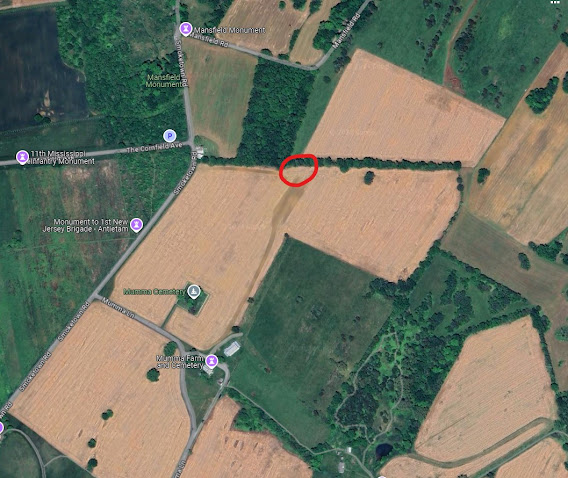

According to the Elliot map of burials at Antietam, two of the 88th’s ten dead were hastily buried just north of the Mumma Farm where there used to be a road. Thanks to battlefield preservation, it may have been the spot circled in the overhead map.