The on thing that still blows my mind to this day is just our sheer access to things. I think the kids of the youngest generations take this for granted. If you wanted to research the Civil War in the 80's and 90s you had to wait until you saw a documentary on TV or go to a library to find a book and most of the time they didn't have the exact thing you were looking for.

Today however you can order the exact book on Amazon or browse E library's for old and ancient books. You could even read them on your watch "Dick Tracy" style. (The older folks will explain that one to you kids). The sheer amount of information at your fingertips is unbelievable.

Because of this unprecedented access I get to peruse publications, speeches and documents about the Civil War era that the past day researcher may have taken years to acquire if ever. I've been reading the "Rebellion Record, A Diary of American Event" written in 1861 and "Harpers Weekly" and "Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspapers" for years and they have helped immensely with my research. They give you a good snapshot of the times and the attitudes of the citizens back then.

One thing that was extremely present in all these old publications was Poetry. You couldn't look at a newspaper or any other sort of publication without poetry being front and center.

Faith Barret in her book "To Fight Aloud is Very Brave" said that 19th Century writers used poetry to navigate a hotbed of political and social pitfall's and argues that the poetry and writing of the day was destabilizing and influential (ala Uncle Toms Cabin)

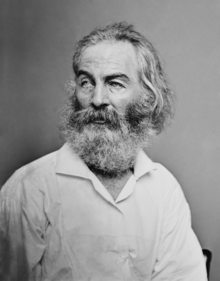

The 19th Century spawned such writers as Walt Whitman, Emily Dickenson, Frances Harper, Herman Melville and Ralph Waldo Emmerson among others.

That being said when I was coming up with some of my presentations for this project I wanted to feature a bit of period poetry to end the night on.

The first that came to mind was a poem called "A Soldiers Letter" some versions of it were called "The Boy Who Wore the Blue" which has been attributed to a few different authors including Joseph Pagett

This poem was recited by heart by 104 year old Daisy Turner poet and story teller and daughter of an enslaved father on Ken Burns "Civil War" series

Of all the poems I've read from that period I feel this one reflected the American soldier the best and paints a picture of the hardships and heartaches that so many of those brave men had to endure so I added it to my presentation.

I have added Mary C Hovey's version from the Rebellion Record Volume 8 here

Dear madam, I'm a soldier, and my speech is rough and plain;

I'm not much used to writing, and I hate to give you pain;

But I promised that I'd do it-he thought it might be so,

If it came from one who loved him, perhaps 'twould ease the blow--

By this time you must surely guess the truth I fain would hide,

And you'll pardon a rough soldier's words, while I tell you how he died.

'Twas the night before the battle, and in our crowded tent

More than one brave boy was sobbing, and many a knee was bent;

For we knew not, when the morrow, with its bloody work, was done,

How many that were seated there, should see its setting sun.

'Twas not so much for self they cared, as for the loved at home;

And it's always worse to think of than to hear the cannon boom.

'Twas then we left the crowded tent, your soldier-boy and I,

And we both breathed freer, standing underneath the clear blue sky.

I was more than ten years older, but he seemed to take to me,

And oftener than the younger ones, he sought my company.

He seemed to want to talk of home and those he held most dear;

And though I'd none to talk of, yet I always loved to hear.

So then he told me, on that night, of the time he came away,

And how you sorely grieved for him, but would not let him stay;

And how his one fond hope had been, that when this war was through,

He might go back with honor to his friends at home and you.

He named his sisters one by one, and then a deep flush came,

While he told me of another, but did not speak her name.

And then he said: “Dear Robert, it may be that I shall fall,

And will you write to them at home how I loved and spoke of all?”

So I promised, but I did not think the time would come so soon.

The fight was just three days ago — he died to-day at noon.

It seems so sad that one so loved should reach the fatal bourn,

While I should still be living here, who had no friends to mourn.

It was in the morrow's battle. Fast rained the shot and shell;

He was fighting close beside me, and I saw him when he fell.

So then I took him in my arms, and laid him on the grass.--

'Twas going against orders, but I think they'll let it pass.

'Twas a Minie ball that struck him; it entered at the side,

And they did not think it fatal till the morning that he died.

So when he found that he must go, he called me to his bed,

And said: ”You'll not forget to write when you hear that I am dead?

And you'll tell them how I loved them and bid them all good-by?

Say I tried to do the best I could, and did not fear to die;

And underneath my pillow there's a curl of golden hair;

There's a name upon the paper; send it to my mother's care.

”Last night I wanted so to live; I seemed so young to go;

Last week I passed my birthday — I was but nineteen, you know--

When I thought of all I'd planned to do, it seemed so hard to die;

But then I prayed to God for grace, and my cares are all gone by.“

And here his voice grew weaker, and he partly raised his head,

And whispered, “Good-by, mother!” and so your boy was dead!

I wrapped his cloak around him, and we bore him out to-night,

And laid him by a clump of trees, where the moon was shining bright,

And we carved him out a headboard as skilful as we could;

If you should wish to find it, I can tell you where it stood.

I send you back his hymn-book, and the cap he used to wear,

And a lock, I cut the night before, of his bright, curling hair.

I send you back his Bible. The night before he died,

We turned its leaves together, as I read it by his side.

I've kept the belt he always wore; he told me so to do;

It has a hole upon the side--'tis where the ball went through.

So now I've done his bidding; there's nothing more to tell;

But I shall always mourn with you the boy we loved so well.

No comments:

Post a Comment